Who is a comic book screenwriter?

The script in comics – its importance

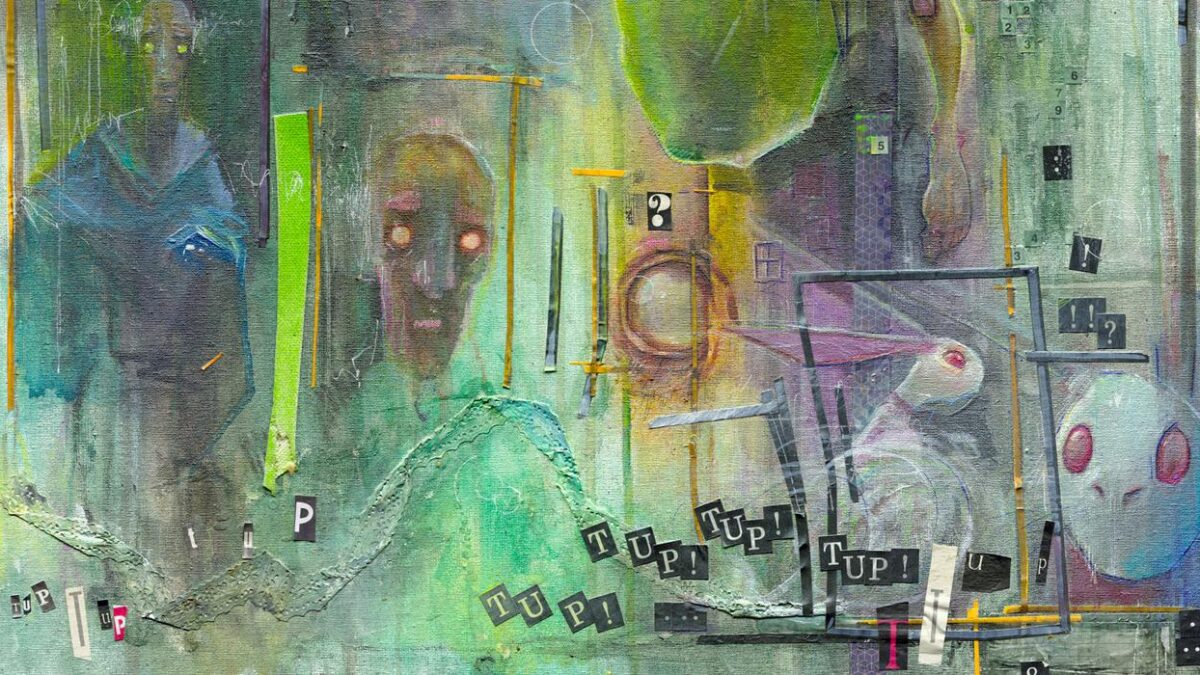

Tales from the Ark - Visions. Karol Weber/Gedeon

Comic book duos consisting of a screenwriter and an artist have been known for a long time, to mention the creator of the famous "American Splendor", Harvey Pakar, and cartoonist Robert Crumb. Accidentally, in the case of this pair, cooperation with a comic screenwriter turned out to be something special - the fact that Crumb lived not far from Pekar, the men met, and Pekar could observe his neighbor's work made him try his hand at comics in the first place. Pekar created scripts, Crumb, author of the famous adult comic strip about Fritz the cat, transferred them to paper.

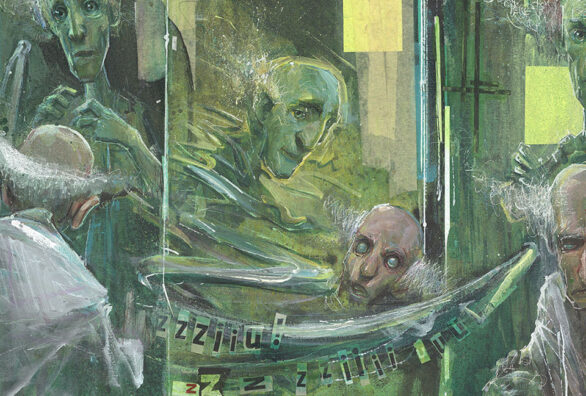

Tales from the Ark - Authority. Karol Weber/Gedeon

Also, the character of "American Splendor" is, in a way, an initiative of Crumb, who persuaded a friend to create an autobiography that is reflective, but daily and far from moralistic in tone. In this way, the collaboration with the comic screenwriter contributed to the creation of an entirely new trend, close to the American realist novel. Pekar obsessively strived to present a fact-filled reality, and so was his "American Splendor" - each story is an immersion into an excerpt of someone's life. He knew how to do it engagingly, although he did not at all invite the reader into a world of horror or an alternative fantastic reality.

Why do we devote so much space to Pekar and Crumb's collaboration? First of all, because it is an excellent example of collaboration between a cartoonist and a comic book writer. But this cooperation does not always have to be based on a collegial relationship - Pekar himself, to illustrate the next "American Splendor" stories, was supposed to look for cartoonists in a not-so-subtle way: calling them and harassing them until they agreed to illustrate the next story. Whether this is a good method - not for us to judge. Although today, instead of the phone, social media will probably be much more useful. We are far from encouraging message harassment, but indeed online it is relatively easy to find contacts to artists, drawing comics. If the conversations go well, both parties like the story being told, there is nothing to prevent an agreement.

However, such a comic book created in cooperation with a comic book writer poses a kind of challenge. After all, in the world of comics there is no shortage of creators who are responsible for both the visual layer and the story in their works. Then, it is known, the matter is simple, because the artist knows very well what and how he wanted to show. The situation is different when the illustrator transfers to paper or canvas the vision of the script author. Then the most important thing in cooperation with a comic book writer is clear communication. Without it, both parties will quickly become entangled, dissatisfied with the results, and ultimately frustrated.

That's why it's worth remembering that at the beginning of the joint work certain arrangements need to be made, including how the script will look like, so whether, for example, a short story will be written in the first phase, and only it will be dissected in the form of a script or screenplay. It is also important how the author will write down the technical instructions for the illustrator, or whether the division of scenes and frames will be on the part of the comic scriptwriter or done in cooperation. If the screenwriter assigns didascalia and comments to the cartoonist, the cartoonist should know about it right away in order to get the best feel for the story itself and, in the process, learn the author's intentions. Also, if the comic scriptwriter has planned any of the frames or their series in a particular way, for example, as three consecutive dynamic vertical frames, he must find a method to clearly communicate the vision from his own head to the cartoonist. We, from experience, recommend just comments plus a clear notation in a given place of the text as didascalia. In this case, a system of color-coded text clues for the illustrator works well - then his eye will quickly find the necessary information, and the screenwriter's expectations will not mismatch with the execution.

Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately?) we will not give ready-made solutions and one right path of cooperation with a comic book writer. This is always a relationship between two individuals with an artistic bent, so it is understandable that each such comic duo can work on their own individual terms. For there are screenwriters who stop at the script, there are those who not only work out the finest details in the script, but also happen to make rough sketches. Cartoonists also work variously - some take the script or screenplay for a long time, only to return with a complete work. Others are in constant contact with the screenwriter, asking for details, agreeing on the smallest details. The style of cooperation depends on the personality, and none is worse than the other. The most important thing is that it works, and ultimately leads to the creation of a comic book in accordance with the author's intentions.

We have already mentioned that many cartoonists choose to work on comics on their own, creating both the illustration and the whole story presented. With what results? Varies. There are times when it is really good, especially when the drawings are at such a level that the reader will not pay particular attention to the average quality of the storyline anyway, to mention the works of Eric Powell. Because also from comics one does not require the level of a world-class work of fiction, comics is a fusion of literature and visual arts with a great predominance of the latter. But there are also cartoonists who are completely unable to cope with the creation of stories, in which case cooperation with a comic scriptwriter gives a boost. By the way, it is often the screenwriter who is the one who is active, striving for the publication of the work, and the cartoonist can at this time focus on what is the essence of his work - art. At the same time, the role of the screenwriter is quite thankless, because ultimately the comic in the minds of readers remains primarily the work of the illustrator.

Related posts

Warning: Undefined variable $post_id in /home/klient.dhosting.pl/sprproject/devkomiks.sprintproject.eu/public_html/wp-content/themes/betheme-child/includes/content-single.php on line 379

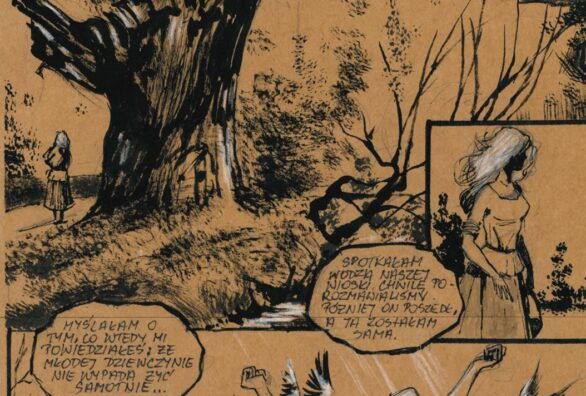

Two Worlds - Rite of Passage. Karol Weber/Artur Biernacki

Warning: Undefined variable $post_id in /home/klient.dhosting.pl/sprproject/devkomiks.sprintproject.eu/public_html/wp-content/themes/betheme-child/includes/content-single.php on line 379

Tales from the Ark - Visions. Karol Weber/Gedeon