The script in comics – its importance

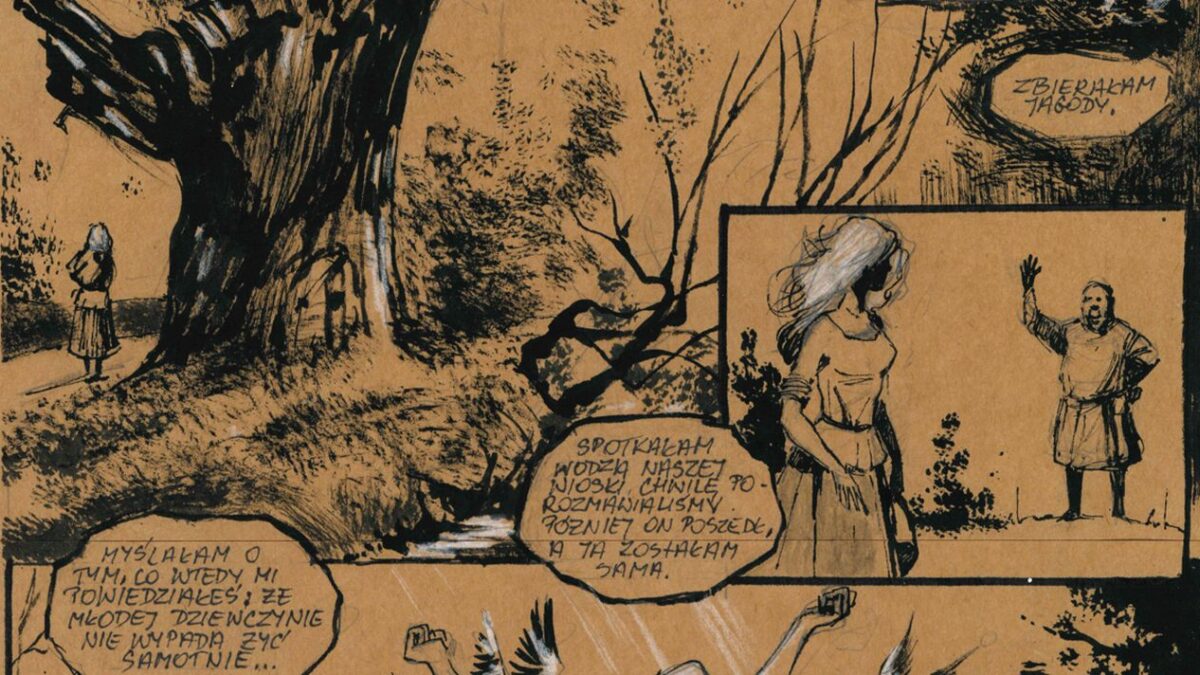

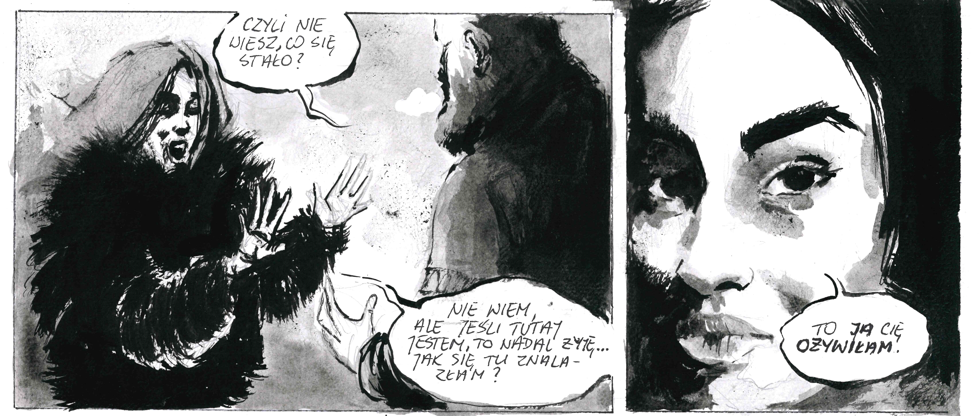

Two Worlds - Rite of Passage. Karol Weber/Artur Biernacki

The script for a comic book is like a canvass, like an architectural design, on the basis of which the contractor-drawer will give it the final shape. However, this shape, before it takes on a real dimension, is born much earlier in the head of the comic screenwriter. Sometimes the author of the script for a comic book is also the creator of its visual layer, but this is not the rule. Therefore, if the final work is the fruit of cooperation between a comic book writer and a painter, illustrator or graphic designer, the question: how to write a script for a comic book? - becomes more complicated. For it requires a double answer: how to write to make the script interesting and the story engaging from the reader's perspective? And also: how to write a script for a comic book so that the vision of the scriptwriter is clear to the cartoonist, so what technical solutions to use, what form to give to the script and how to describe the characters, so that what will be created on paper (or stretcher or on the screen) coincides with the vision that was created in the head of the script writer?

Two Worlds - Rite of Passage. Karol Weber/Artur Biernacki

So, let's try to answer the first of the questions, that is, how to approach the story to make it engaging for the viewer. The same as for any other literary work - original, creative, ambitious, but also with some knowledge of the field we intend to practice. The first and most important issue remains the idea. This idea can have very different sources: perhaps it was inspired by some interesting story, perhaps the prototype of a place or person proved so fascinating to the creator that he decided to build a story around it. Or perhaps it was simply born out of a need to write or came to mind just like that, as a conglomeration of various pop culture creations? This is not particularly important, anyway, as what matters is that the idea is as catchy as it is fresh.

And this is where all the white on white knowledge comes in. Yes, knowledge - without it, you won't have a clue that your absolutely unique idea is a carbon copy of an already existing concept or a patchwork of patterns, characters and motifs that have been in popular literature for years. That's why we're giving an important tip here: before you start writing, read, absorb the world you're about to enter, get to know it, and tame it so that you know whether the idea that dawned in your head is actually yours, or whether it's merely a reflection of something you've read and memorized. Does this mean that every idea must be hyper-original? No, because every source will eventually be exhausted. However, it is good not to copy one-to-one worlds or characters that another author has created. That's why an idea is only the beginning, you need to give it time, let it mature, take shape - precisely so that you don't write everything that comes to mind in a hurry, and what you hear likes to come to your head. The work will not be given originality by trite motifs, otherwise familiar worlds and trite dialogues.

The idea for a script for a comic book should somehow define the scope of the world presented. Therefore, once the main idea is clarified, it is a good time to ask yourself some important questions. Here it is a good idea to use a set well known to all journalists, that is, to look in your head for answers to the questions: what, who, where, when, how and for what? This may seem trivial, but trust us, it is not so at all. The idea is an idea, but now it's time to create a coherent, interesting story. And in order to create one, you need a time, place, plot and characters.

The latter are worth focusing on in a special way, because they also occupy a unique position in a script for a comic book. But before the actual script is created, it is good to create a sketch of it, that is, an outline, on the basis of which we will continue to work. Everyone who appears in this relatively short form, which is a comic book, should be for something. Let each character contribute something, otherwise instead of content, we will get the effect of chaos and unnecessary excess of names and people. If we are already constructing a character, let's think it over - give it characteristics, distinctive features, create its history and place in the reality we have created. Let's devote those 3-4 lines of text to her, describing her appearance, distinguishing features and character traits, maybe roughly the role she will play in the story. For now we will do without details, these will appear only at the stage of constructing the script for the comic book.

The same, moreover, is true of the story itself. When writing, it's not worth rushing, here piecework never works. Let there be fewer words, but let them carry important content. In general, the presented story should not be a blowout - even if its canvass is simple, behind this seemingly banal facade, there should be a story with universal values. This is how literary works are defined in literary studies, after all, there are millions of books coming out every year, and yet very few pretend to be works. Yes, but they are those that, in addition to the story, touch the tender string of universal values, such as respect, honesty, responsibility, love, civil courage, solidarity or friendship.

But does a comic book, or in fact a certain pop-cultural pleasure, have to be an ambitious work? No, but neither should it insult the intelligence of readers with meaningless stories. Let American super-productions, such as "Top Gun," serve as an example here, where, amidst airplane evolutions and a procession of special effects, love, friendship, solidarity, courage appear - and, in essence, these are what ultimately win out over evil urges. Is this the only right way? No, but certainly a trail that is capable of evoking engagement in the reader, and after all, that's what writing is all about.

A screenplay can be useful for one's own work, but ultimately a script for a comic book will still be necessary. If a cartoonist, graphic designer, painter or whoever is responsible for the visual layer of the project is to get anything out of it, the script for the comic simply has to be readable. Therefore, it is useful to use the classic division into scenes and frames, sometimes for your purposes you can abbreviate the purpose of a scene so that you do not lose sight of it, developing the plot and dialogues. However, this is not the only method of creating a script for a comic book, some creators, especially when the writer is not a cartoonist, rely on the story form, and only later the scenes and frames consult with a visual artist.

No matter what form of script for a comic book you opt for, remember that with the tapping of the word "end" on the keyboard, the screenwriter's work does not end at all. Now comes the time to make the first corrections, that is, to consider whether the full potential of the characters and scenes has been used, whether any plot gaps and understatements or, worse, factual errors remain, and, above all, whether the story is coherent enough that the reader will not feel lost at some point. This is also a good time to remodel scenes if necessary, or even completely rebuild them if you deem it necessary to improve, for example, the pace of the plot.

No, it's still not the end of the job - after the first ones comes the time for second revisions. You can try to do them yourself, but first of all, you probably already have the reading and rewriting of your own content above your ears, and secondly, your own mistakes are unlikely to be noticed anyway, since you feel an emotional attachment to the text to some degree. At this stage of polishing the text, it's a good idea to entrust it to someone trusted to look at the logic and rhythm of the text, and perhaps assist with editing and proofreading. Only after all of this, let the final reading, the final touches and the final finish take place. You must decide when you say enough to the corrections, otherwise you will chisel the text indefinitely.

Before the text is laid out on scenes and frames, it is sometimes practiced to lay it out on storyboards. It's worth remembering that you are the one who ultimately decides on their shape, because when it comes to drawing, creativity is not limited by the guidelines of computer programs. So the frames can be oblong, square, rectangular, whatever you want. However, their shape and intensity connotes the course of the plot - because try to always remember, even if you are only a screenwriter or comic book writer, that you are moving on the border of arts, and this artistic fusion can be as fascinating as dangerous, because instead of one field, it makes you understand the specifics of both.

Related posts

Warning: Undefined variable $post_id in /home/klient.dhosting.pl/sprproject/devkomiks.sprintproject.eu/public_html/wp-content/themes/betheme-child/includes/content-single.php on line 379

Tales from the Ark - Visions. Karol Weber/Gedeon

Warning: Undefined variable $post_id in /home/klient.dhosting.pl/sprproject/devkomiks.sprintproject.eu/public_html/wp-content/themes/betheme-child/includes/content-single.php on line 379

Tales from the Ark - Visions. Karol Weber/Gedeon